Dharmachari Suḍāka

Co-Founder of Bodhiyoga International

13 November 2019

Yoga. mindfulness and meditation are enjoying more and more popularity these days. There is a richness, breadth and depth of understanding evolving around these ancient spiritual practices of hathayoga (psycho-physical disciplines) as well as mindfulness and meditation. I want to draw out a few threads that are current in my own practice and teaching. This has especially come to light since establishing and running a yoga teacher training based on Buddhist Mindfulness teachings called Bodhiyoga International.

I want to explore three aspects of Yoga in particular.

- Yoga as therapy, in terms of the health giving properties of yoga asana (postures) kriyas (cleansing techniques) and pranayamas (breath work).

- Yoga as a support to transformation of our consciousness emphasising the more internal meditative and reflective aspect of yoga practice.

- Teaching yoga to others, the altruistic dimension of yoga teaching work. yoga as service to others.

I write this as a continuing student of yoga having now been practicing for 30 years since my teen age and over the last decade, as a teacher of teachers of yoga. I want to appeal to wider audience in order to explain what yoga is (from my experience of course). Yoga is becoming ubiquitous, appearing far and wide and taken up by many. There is an explosion of interest in the modern world as much as in its cultural home of India as both East and West, from Latin America to Japan. I want to draw out what are my three primary interests in yoga and also explain what we do in our Bodhiyoga teacher training.

1. Yoga as therapy

Here I want to point out what is obvious. Perhaps the primary focus for practitioners these days is to optimise and improve their health. Yoga posture work and its associated practices like breathing exercises and eating recommendations forms part of a long tradition of medicine in India known as Ayurveda (that which lengthens and promotes (Ayur), life (Veda). There is an incredibly rich source of studies done over millennia on what helps and what hinders human health and well being as well as approaches to healing illness, diseases and conditions of both physical and mental health. Very clearly after a yoga class doing a few stretches and some toning we feel better. This medicinal aspect of yoga is tremendously important to us as we live in a time where health continues to be a problem even with all the material advances that we have made.

Lack of exercise, unskilful eating habits, and lack of contentment and happiness are all common issues today and yoga has much to offer on this level. In fact in the hands of a skilled yoga teacher we can help heal many physical and emotional health conditions.

There is also much possibility for overlap and mutual understanding through modern medicine and other ancient systems of health giving like Chinese medicine, and more “primitive” folkloric herb cures and so on. Fortunately many health workers both conventional and alternative are exploring thoroughly these connections and there is much work yet to be done.

In our Bodhiyoga training we emphasise safe and technically skilful posture work paying especial attention to what could be called functional anatomy. Functional anatomy takes into account of the bodies individual capabilities in terms of strength, flexibility and stamina and adjusting the posture work accordingly to each student. Rather than imposing a predetermined idea of what the body should look like based in a photo of a yoga pose we respect our own bodies and explore the pose from the inside out.

The therapeutic application of specific body and breath work, we draw out even more in the 500 hour Advanced training Continuing Prosessional Development) for yoga existing teachers. We examine postures and sequences to address particular muscular-skeletal problems like low back conditions. This work has been developed through Krishnamacharya’s disciples Desikachar and BKS. Iyengar in India and “Western” teachers like Gary Kraftsow and Mira Mehta amongst many others.

2. Yoga and the transformation of consciousness

Yoga, so far as we can see, has a long, long story. There are even terracota images of the human form sat in a cross legged posture with animals dancing over the head from excavations from Harappa and Mohenjo-daro possibly meditative practices from the Indus Valley civilisation (

3300-1300 BCE). We cannot really know what was going then, only speculate. There is a limestone statuette from Mohenjo-daro that seems to represent meditative pose. (or maybe someone squatting down). Were they meditating? Were they communing with the natural world around them?

Then we have the written Scriptural tradition.

The sages of old reference the Rg Veda (around 1500 BCE), perhaps the oldest written spiritual text that exists in connection with yoga. They are hymns that predominantly discuss cosmology and praise deities. As a spiritual discipline the term “yoga” appeared for probably the first time in the Taittirya Upanishad, which dates from the sixth century BCE.

We then come to the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali. 196 aphorisms on yoga. This is notable treatise from the Samkhya school of Hindu philosophy estimated to have arisen somewhere between fifth century BCE and the fourth century CE. with more scholars accepting dates between the second and fourth century CE. This scripture is an important and crucial reference point for most proponents of yoga these days. Unfortunately it is a terse, poetic text with little mention of the word asana (posture) dealing principally with the issue of the transformation of consciousness through a meditative process. Famously we hear “Yogas citta-vritti-nirodhah”. Yoga is the restraint of the mental modifications.

Depending on who translates and comments on the text and their world and philosophical view the text can be interpreted very differently. Due to its poetic nature we can give a theistic dualistic interpretation bringing in God and Brahma, atman and the soul or we can relate to it from a non-dualistic perspective, translating terms like “isvara pranidhara” more like “revelation of one’s inner nature” . In fact it appears to move between these two perspectives through the Sutra. There is no comment on the elaborate posture work that we see today. Curiously, meditation is not even taken that seriously in modern day yoga circles, even though Patanjali points so strongly to the practice.

The posture referred to by Patanjali is that which is steady and easeful . This idea was then developed in other schools for example Vyasa in his commentary of 12 poses, all seated like Padamasana (lotus pose) to support meditation practice.

A variety of Yoga posture work which we could consider more modern is shown in much later texts, as in the Hatha Yoga Pradikipa (84 poses, 15th century), the Gheranda Samhita (32 poses, 17th century) or Shiva Samhita (names 84 poses of which only 4 are described in detail, 16th-18th century).

With these treatises we enter the world of yoga tantra. And we enter the world of various methods of exploration of consciousness through systems of pranayama, breath work, nadir and chakras, the channels and energy centres.

My personal journey towards yoga and meditation

My intuition is that having a teacher or guru will be indispensable to delve meaningfully into these realms via Tantric Yoga. I was drawn to meditation as taught in the Buddhist tradition. The simplicity of the Buddha seated in meditation attracted me. Initially I trained under Theravada Buddhist teachers in Thailand through a number of intensive silent retreats is various Monasteries in the north and south of the country in the early 1990’s.

Returning to Europe I sought out teaching through the modern day practitioners of the Triratna Buddhist Order. Hence my yoga posture work developed alongside a deepening and broadening experience of meditation in the wider Buddhist practice context that includes ethics and Wisdom teachings. Especially relevant here is the teaching on Mindfulness through the Satipatthana Sutta.

The Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta (The Discourse on the Establishing of Mindfulness), and the subsequently created Mahāsatipaṭṭhāna Sutta, (The Great Discourse on the Establishing of Mindfulness), are two of the most celebrated and widely studied discourses in the Pāli Canon acting as the foundation for contemporary meditational practice. These suttas (discourses) stress the practice of sati (mindfulness) “for the purification of beings, for the overcoming of sorrow and lamentation, for the extinguishing of suffering and grief, for walking on the path of truth, for the realization of nibbāna. (Awakening).

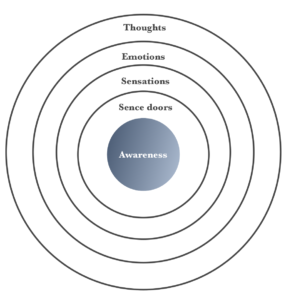

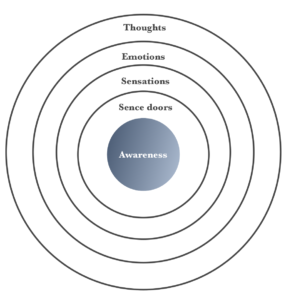

Mindfulness – Sati – layers of experience

Typically the Satipatthana teaching is represented as four areas (body (ruoa), sensations or hedonic tone (vedana), heart-mind experience (citta) and mind-contents (dhamma) of which we develop awareness. Ultimately with the intention of seeing these aspects of our experience as not fixed, impermanent, transient phenomena with the invitation to profoundly “let go”. Personally I have found it helpful, to avoid “compartmentalising” my experience to see these various aspects as “layers” of experience which interact with each other.

- We have then Awareness at the heart of experience, of course also subject to change, coming and going as it does, more refined, more gross.

- We relate directly to the world through the sense doors, hearing, seeing, tasting, touching, smelling and “seeing with the mind”, the mind as a sixth sense organ.

- Sensations inevitably arise, pleasant, painful or more neutral

- Emotions have their own dynamic too, arising in relation to sensations, as in not wanting painful or uncomfortable experience or wanting more of pleasant sensation and becoming attached even or addicted to certain sensations and experiences. We also develop emotional habits or tendencies as well as those that we somehow inherit from birth, which in turn conditions sensations. Just recall the last time your got angry, was a there not a physical feeling tone the anger.

- Thoughts arise, come and go, where do they come from, where do they go? Again, we can get into habitual ways and pathways of thinking, there are those repetitive insistent thought patterns we can often suffer.

As we are practicing awareness throughout the day and more formally during sessions of yoga and meditation practice we can look at the various layers and watch and feel the interplay between them. A transformational process can begin, preceded by awareness, where we essentially withdraw energy form tendencies that are causing us harm and promoting new habits that lead to greater well being and contentment.

Mindfulness Yoga – A contemplative practice

Developing awareness is that first step – how to do that?

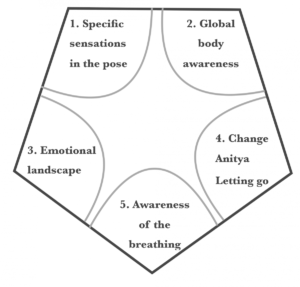

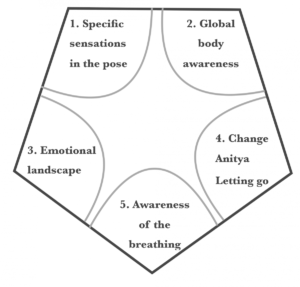

The five key Mindfulness practices in Bodhiyoga Mindfulness yoga are drawn out of the more complex set of instructions outlined in the Satipatthana Sutta. As “yogis” we are already orientated towards our body, so we develop the practice from there.

1. Awareness of the specific sensations associated with your experience in the pose.

2. Global awareness of the whole body

3. Awareness of the emotional landscape.

4. Awareness of our changing experience. “Anitya”. Impermanence. Letting go.

5. Anchoring awareness in the breath. Ana Pana Sati.

What we do in Bodhiyoga?

Our approach is a return to a more traditional emphasis on meditation and working with the mind. We combine an anatomy based approach to alignment in the postures respecting the limitations and possibilities of each persons body with an application of Mindfulness to what we are doing.

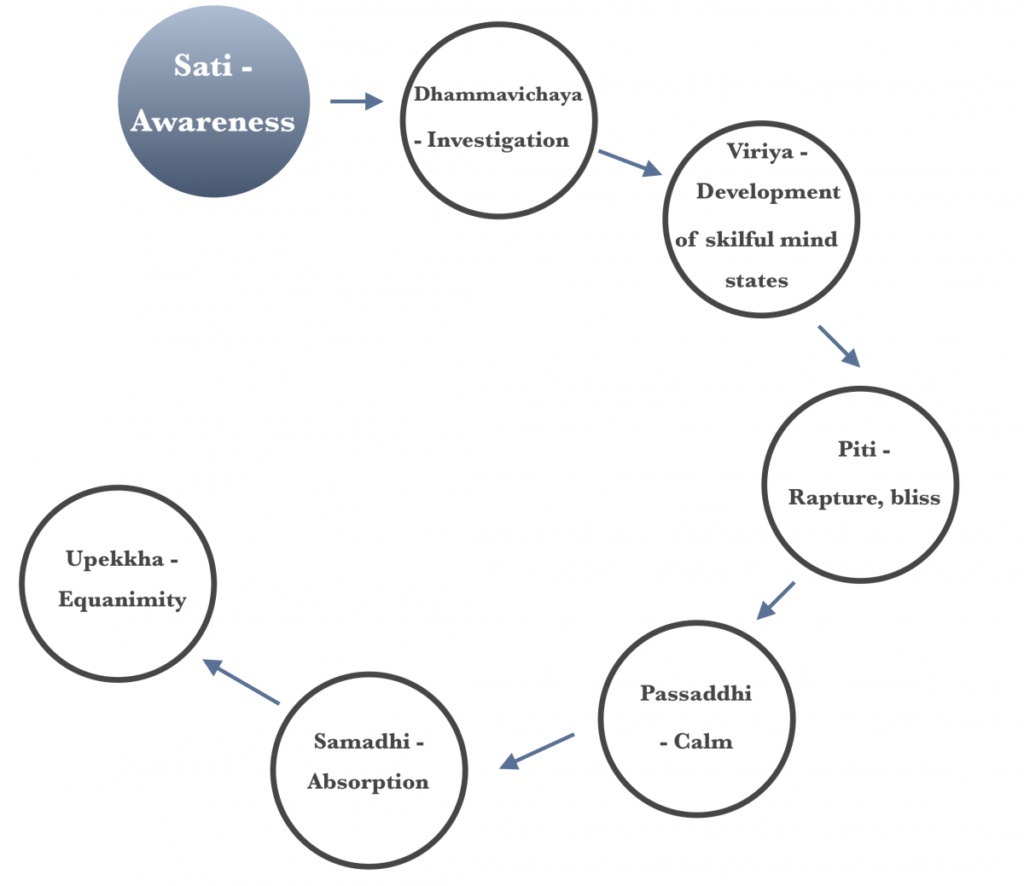

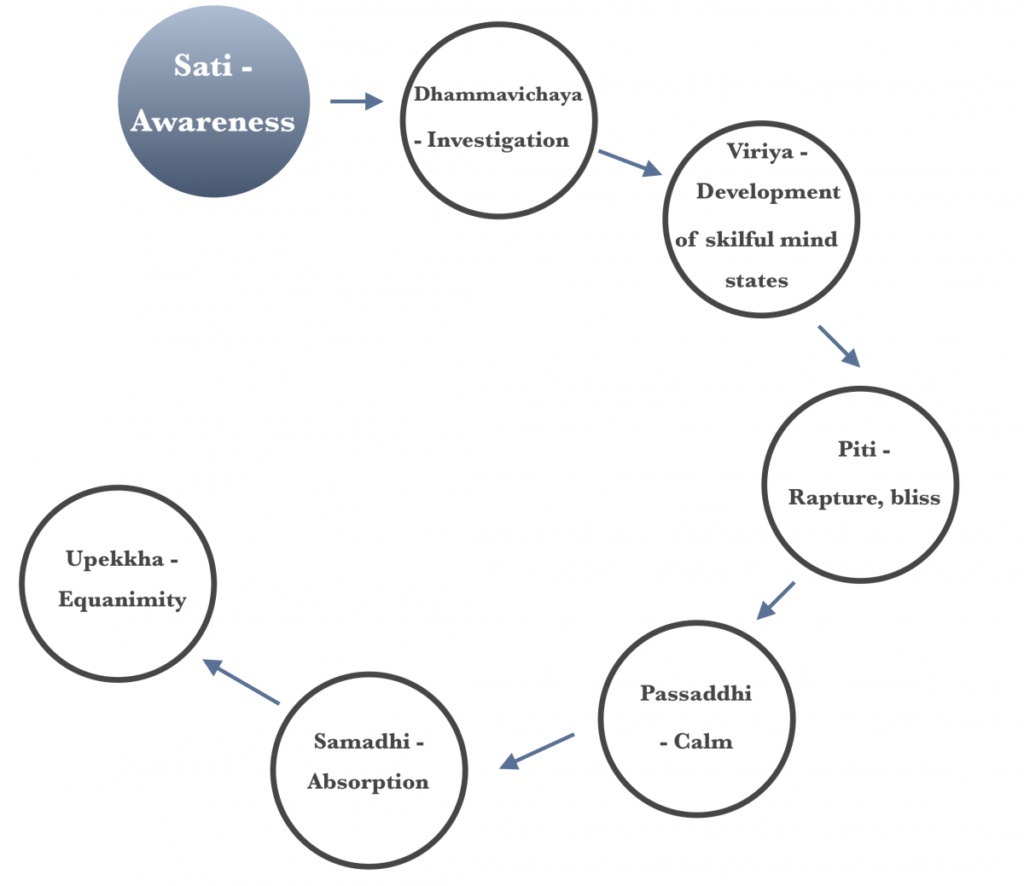

This awareness practice allows the practitioner to go deeper into their experience and enter into a process of transformation. This journey to a more Awakened existence is described in the Satipatthana Sutta by the seven factors of Awakening or Bodhiyangas.

Most likely, most of the time, most of us are working up to the first three factors, developing a more skilful flow of mind states and doing our best to avoid unskilful ones. (Viriya)…..

3. Teaching yoga as an altruistic pursuit

The world is in crisis. The image of the world as a Burning House, from the White Lotus Sutra (first century BCE) seems more relevant than ever.

What can we offer as yoga teachers?

When we are running around town giving our classes its easy to see ourselves as a glorified Physical Education instructor. As we have seen yoga, if judiciously applied can have tremendous benefits for the health of practitioners. (Conversely it can do harm if we force the body or mind without sensitivity and intelligence). Yoga can promote health and wellbeing and that alone is sufficient reason to adopt the practice and teach.

Yoga can be a gateway for many people to have a more complete experience of themselves. Getting in touch with their body, heart and mind is invaluable in a society where much of our activities are orientated around a more distracted frenetic rhythm of being, stress inducing, leading to unhappiness and discontent. Our yoga classes potentially provide each practitioner with a space to be calmly with themselves at the same time sharing that space with others. Yoga has a social aspect to it, being alone with others.

Becoming more aware of ourselves can lead to becoming more aware of others and the world around us.

If you feel drawn to supporting others to make that step into greater awareness of themselves, go ahead and share your love and enthusiasm for yoga, mindfulness practice and meditation.

Yoga is not going to save the world on its own. Lets remember that for those of us practicing, it is a privilege to have the time and energy to dedicate ourselves to our own well being and not just be running around trying to make ends meet and get food onto the table, which for the vast majority of human can be the primary preoccupation.

I wish to affirm that yoga teaching can be a wonderful contribution to the society and any movement that helps others to become more aware, more sensitive and more kind is one way to shine a light into the darkness.

Yoga, so far as we can see, has a long, long story. There are even terracota images of the human form sat in a cross legged posture with animals dancing over the head from excavations from Harappa and Mohenjo-daro possibly meditative practices from the Indus Valley civilisation (3300-1300 BCE). We cannot really know what was going then, only speculate. There is a limestone statuette from Mohenjo-daro that seems to represent meditative pose. (or maybe someone squatting down). Were they meditating? Were they communing with the natural world around them?

Yoga, so far as we can see, has a long, long story. There are even terracota images of the human form sat in a cross legged posture with animals dancing over the head from excavations from Harappa and Mohenjo-daro possibly meditative practices from the Indus Valley civilisation (3300-1300 BCE). We cannot really know what was going then, only speculate. There is a limestone statuette from Mohenjo-daro that seems to represent meditative pose. (or maybe someone squatting down). Were they meditating? Were they communing with the natural world around them?